I first encountered Robert Caldwell after Udayanidhi Stalin’s statements against Sanathana Dharma caused social media to explode. Caldwell was buried in the comments section of a YouTube video on his statements and their context.

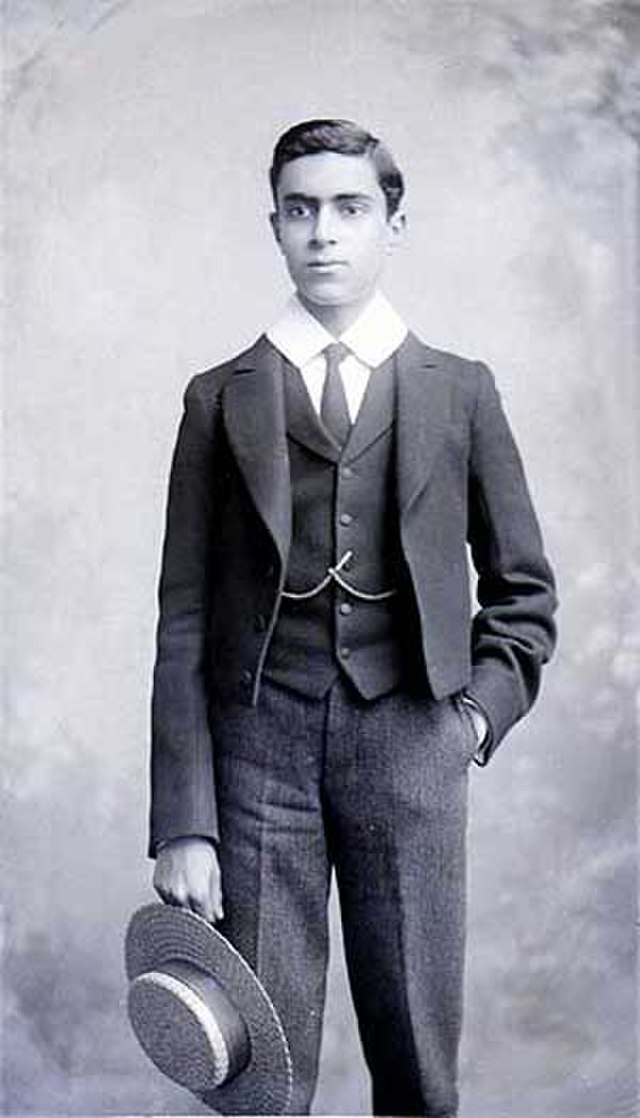

If, like me, you don’t know much about the man – this is Robert Caldwell.

Look at his wise eyes, his luxurious, well-tended beard – a sober Santa on a healthy diet of South Indian food.

Robert Caldwell was old when this picture was taken, and so looks a little more dignified, but in his youth, it feels like Caldwell was an intense sort of fellow who was interested and curious about everything. He landed in Madras in 1837 with a blazing missionary zeal to bring Christ to the heathen masses of South India. He wanted to do it in the local language – Tamil, perhaps influenced by a German Christian movement called Volkskirche (people’s church). According to the Volkskirche philosophy, the church was for the people who were its members, and so needed to be based on the culture, language, and tradition of the local population. In 1841, Caldwell walked (walked!) from Madras to Tirunelveli, where he would later serve as Bishop of Tirunelveli. In 1844, he married Eliza Mault, the daughter of another missionary. Eliza, who was born in Nagercoil, bore Caldwell seven children and joined in proselytizing local Tamil women. This brief biographical outline was enough to impress upon me that the western missionaries of the 19th century were made of different stuff. They were wandering about the hottest parts of India, determined to bring Christ and salvation to people, in a time before penicillin, or even antiseptic. A lot of them trudged around, lugging what Rudyard Kipling would call the white man’s burden

( ‘to take up the White Man’s Burden/… to serve [his] captives’ need/… to wait in heavy harness/ on fluttered folk and wild/ – … half devil and half child.’ )

Now, Caldwell was a sort of racist (you’ll see why later) Renaissance man. He was not just a Christian missionary – he was a gifted linguist, anthropologist, and archaeologist. As an archaeologist, he collected palm manuscripts of ancient Tamil literature and dug up the foundations of ancient buildings, funereal urns, and Pandyan coins.

Caldwell, the Shanars and the Dravidian Argument

As an anthropologist, he studied the local Nadars (he called them Shanars). The Shanars made up most of his flock at his congregation in his little village of Idaiyangudi (south of Tirunelveli). Caldwell was particularly interested in the Shanars, whose traditional occupation was to climbing Palmyra palms and collect toddy, because they suffered tremendous caste oppression and discrimination, and were the target audience for most missionary activity.

Untouchables and lowest caste Hindus lived in miserable social and material conditions through almost all of Indian history. Living on the outskirts or of towns and cities, or in separate settlements, they had to endure all kinds of humiliations. The missionaries noticed that the untouchables would hide in ditches or climb trees to prevent polluting the atmosphere as caste Hindus passed them by. In some places, they would maintain specific distances from caste Hindus based on how low they were on the caste hierarchies. If one of them was found violating caste rules could be slashed down with a sword without second thought. Women could have their breasts cut off for not covering them appropriately, and in one reported incident, a man was impaled alive for selling a bullock to a European man in 1772. And of course, they lived in miserable poverty, with no scope of escaping its trappings.

Missionaries provided medical care and education to people cast out by Hindu society for thousands of years. In addition to the services provided, the missionaries introduced them to Christianity, promising them a chance to live in a society of equals (or so they thought and hoped).

Yet, with all the promise of a better life – both now and after death – that Christianity offered, Caldwell’s Shanars did not seem to be converting in the large numbers that Caldwell must have expected.

Part of this was Caldwell’s fault of course. In his book on the Shanars with the impossibly long title – The Tinnevelly Shanars: A Sketch of Their Religion and Their Moral Condition and Characteristics as a caste with special reference to the Facilities and Hindrances to the Progress of Christianity among them, he seemed to go out of his way to insult the Shanars.

He wrote: “I am confident that none can be compared with the Shanars for the dullness of apprehension and confusion of ideas”.

Then, as an example of comparative racist analysis (an intellectually rigorous practice in which you compare your racist judgments about one group with your racist judgments about another group and see who wins) he thought he should let his readers know that “the Negroes [of West Indies were] superior to the Shanars in intellect, energy and vivacity”. The Shanars, he wanted you to know, were worse than the untouchable castes lower than the Shanars, like the Pariars had sharper intellects and better manner of talking (their expressions and pronunciations more accurate) because they had “in their daily business more intimacy with the higher castes than the Shanars have”.

Caldwell must have assumed that the Shanars would never actually read his book, but he was wrong of course. The Shanars, obviously, took offense to someone writing of them with such outrageous prejudice. But, also, Caldwell was saying something else more upsetting. Caldwell was saying that the Shanars did not naturally belong to Brahminical Hinduism. According to him, they were an indigenous people, separate from the Aryan Hindus who had come from the North, and imposed Vedic Hinduism, Sanskrit, and the caste system on the locals. Caldwell introduced the idea that Dravidian languages (like Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Tulu, etc) were indigenous languages that developed separately from Sanskrit. He was able to support this claim very credibly in his seminal work: A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages

Caldwell felt that Shanars and other lower-caste Hindus were unwilling to part ways with Brahminical Hinduism. One can imagine that they might have feared further social isolation or possibly incurring such bad karma that their next life would be more cursed than this one.

In his book, Caldwell wrote that Vedic Hinduism had been imposed on the indigenous culture of the Dravidians. He claimed that the Brahmins were of Indo-European stock who had colonized the south and installed a harsh social hierarchy upon the society, making sure they were on the top.

Now some of Caldwell’s claims are self-serving. He was trying to draw the Shanars away from the influence of the Brahmins. By stating that the Dravidians had an independent literary and religious history that pre-dated Brahminical influence, Caldwell hoped that the Shanars would feel more free to leave the Brahminical fold and join the Church.

The thing is that Caldwell wasn’t entirely wrong. His linguistic analysis was sound and contemporary and later linguists agreed – Tamil and the Dravidian languages are an independent and indigenous language group. The worship of mother goddesses, animistic forms, and, later, Shaivism, all predate Vedic Hinduism’s arrival in South India. Jainism and Buddhism were in South India before Vedic Hinduism and Brahminism (we know this through Sangam literature’s limited mention of typically Hindu and caste-based topics – many of the earliest Tamil literature were either secular or later credited to Jain and Buddhist poets, or through archaeological evidence).

Regardless of his intention, he wasn’t wrong in highlighting the rich Dravidian cultural history that all Indians should be proud of. The Shanars can’t be faulted for choosing any route out of the utter misery that an oppressive caste system subjected them to.

Without meaning to, Caldwell’s writings laid the bedrock for an anti-Brahminical political movement that demanded social justice and freedom from caste oppression that extended well into the 20th century… and, clearly, the 21st century (the DMK and BJP in Tamil Nadu were on the subject in 2023)

Caldwell served his congregation for fifty years but his legacy has outlived him. Not only did he (along with many other missionaries and linguists, some of whom mentioned Dravidianism before him) introduce Dravidianism to popular discourse, but he also managed to convert most of the local Shanar population by the end of his life. Today, Tirunelveli has one of the largest Christian populations.

Isn’t history funny? A prejudiced colonial missionary became one of the early influencers of the anti-Brahmin movement and social justice movements. What does it matter if the movement tried to help people shrug off oppression thrust on them for millennia?

.jpg?mode=max)